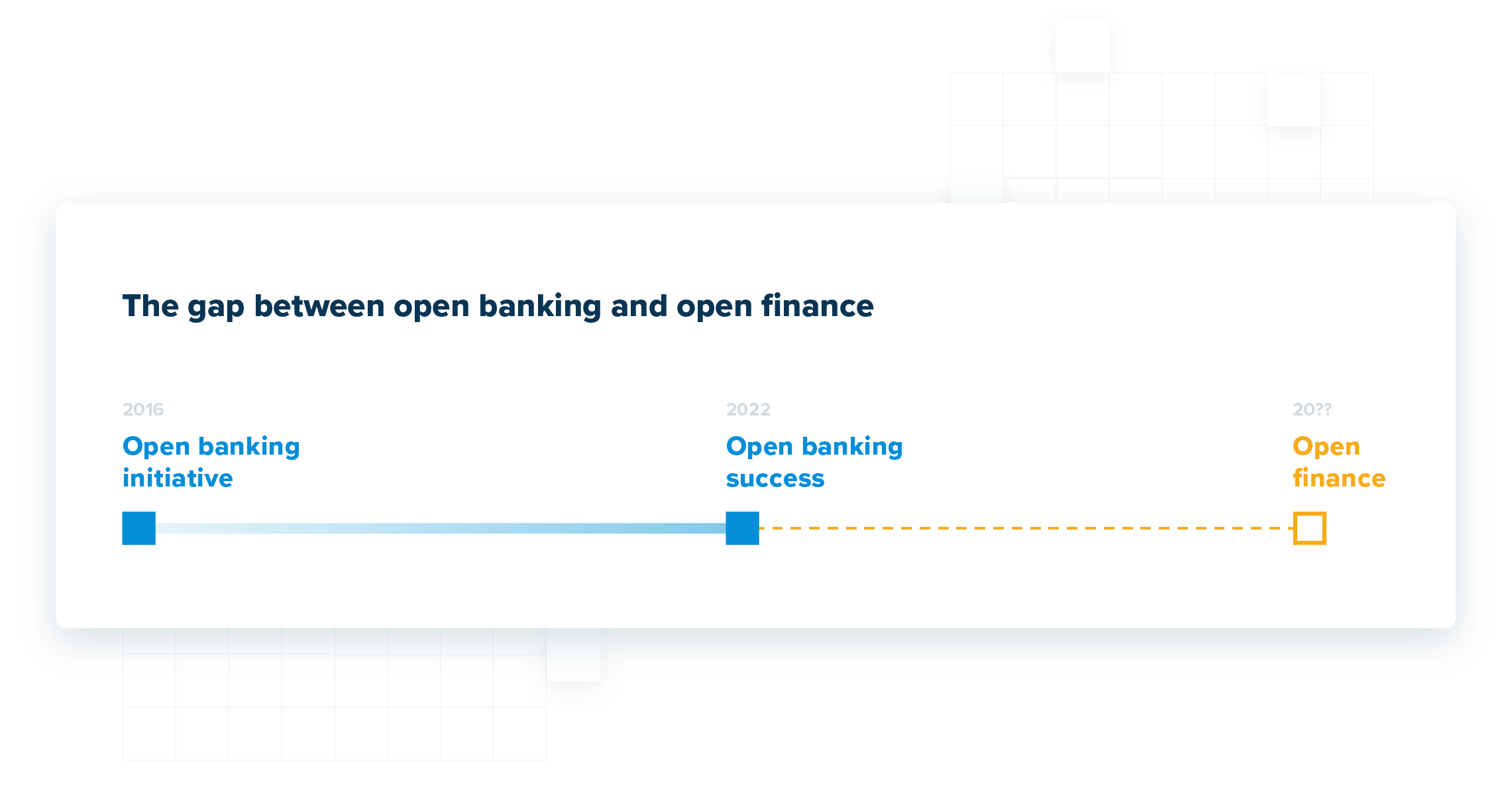

Open banking has brought millions of people a new way to pay and manage their money. Its success in the UK has been underpinned by a dedicated open banking implementation entity, the OBIE. But the OBIE’s roadmap comes to an end in September 2022.

Since 2019, open finance has been discussed as the ‘next big thing’ which will extend open banking principles and benefits to new financial sectors such as savings, investments and pensions. A new ‘Smart Data’ bill introduced in July could pave the way to open finance by enabling authorities to create a new open finance framework. But legislation may take years to come into effect.

So a gap is forming between open banking and open finance, and momentum could be lost. That would be bad for UK’s position as a world leader in fintech, and for the companies relying on timely progress and development of open banking. So why is this happening, and how can we prevent it?

Open banking: an unfinished symphony

Open banking is a regulatory initiative which began with the introduction of legislation (PSD2) in 2016. It gave consumers and businesses the legal right, for the first time, to access their payment accounts via third party providers (TPPs) like TrueLayer.

It enabled TPPs to access data and initiate payments via technology known as application programming interfaces (APIs), which increase security and reduced barriers to entry.

The UK has seen a huge amount of open banking innovation. To date there are 6 million active users, 6 million open banking payments per month and hundreds of new providers offering services to consumers that range from financial management to instant top-ups for investments.

“Right now, a dedicated, independent coordinating function has never been more important.

But there are limitations to open banking that hold back further innovation:

Scope: only current accounts and credit cards are accessible via open banking. Savings, investments, pensions and mortgages are yet to be opened up

Consistency: banks largely determine how open banking works. How much a customer can pay using open banking varies depending on which bank they use

Functionality: while TPPs can initiate single immediate payments, there are limitations on their ability to initiate recurring payments

User experience: while the user experience of open banking has been improving, there are system-based limitations — such as the speed at which banks process API calls, and payments settle — that ultimately impact user experience

Coverage: open banking payments are yet to take off at physical point of sale due to access restrictions to NFC chips (for contactless) and in-store payment terminals

These limitations demonstrate that the job is not finished for open banking. Legislation written in 2016 needs to be revisited and the regulatory approach developed. Right now, a dedicated, independent coordinating function has never been more important.

The OBIE runs out of road

Much of the success of UK open banking is down to the decision to require the largest banks to create a common API standard, and a body to oversee implementation of APIs: the OBIE.

The OBIE was given the power to compel banks to make changes in line with achieving the objectives of the CMA order. This meant that it could push through measures that have increased adoption and usability of open banking.

However, the roadmap of activities planned under the CMA order will come to an end in September. This calls into the question the future of the OBIE itself, as its funding model is also due to expire.

Getting back on track with JROC

That’s why the UK government and regulators have brought together a new Joint Regulatory Oversight Committee (JROC). JROC will oversee the transition of the OBIE to a future entity and develop a vision and strategic roadmap for developing open banking into a programme of work called open banking + until a permanent regulatory framework is in place.

First announced in March 2022, JROC has so far set out its terms of reference, held monthly meetings since May, created a Strategic Working Group (SWG) to engage closely with industry, and appointed an independent chair to that group. An ambitious series of sprints and expert panels have now been announced to feed into the SWG.

JROC's work to resolve the future of the OBIE and design a roadmap to open banking + will be crucial to bridge the gap to open finance.

COVID-19: open finance stalls

The scope of open banking has been in consideration since the FCA published a Call for Input on open finance in 2019.

Understandably, the FCA’s focus in early 2020 turned to supporting financial measures during the COVID-19, and open finance work was put on hold. A feedback statement followed over a year later.

That statement pointed to government legislation on Smart Data as a vehicle for progressing open finance. That legislative process has now started with the publication of the ‘Smart Data’ bill in July.

While there is no mention of open finance in the bill, it’s likely that the legislation will act as an enabler for work by individual government departments, and for any further legislation on open finance.

Can open finance be achieved without legislation?

As the delay to open finance has set in, there has been greater discussion of whether industry can further develop open banking and open finance without regulatory intervention or legislation.

In the EU, the European Payments Council is undertaking a project with this very ambition. It aims to create a scheme where parties pay to access ‘premium’ API functionality that goes beyond what was mandated under PSD2.

In the UK, The Investing and Saving Alliance (TISA) has been working on a set of API standards for savings, investment and pensions products.

“To bridge the gap between the open banking and open finance, we need strong leadership from Government and regulators

A key question for these initiatives is how they will ensure coverage of financial institutions when participation is voluntary. Financial institutions have little incentive to open up valuable data and account functionality to third parties. This is why it took two parallel competition initiatives to make open banking succeed in the UK (PSD2 and the CMA order).

But forcing institutions to open up purely as a compliance exercise also has downsides, as it leads to open banking APIs becoming a cost centre for banks. In some cases, banks maintain APIs for compliance reasons rather than as important products, and this impacts their performance.

It's likely that open finance will succeed through a mixture of compulsion — to secure the upfront investment in, and coverage of, APIs — and commercialisation �— to ensure that financial institutions are incentivised to maintain high performing APIs.

Bridging the gap

To bridge the gap between open banking and open finance, we need strong leadership from Government and regulators. Open banking + needs to be the first priority.

A concerted sprint is needed to ensure we have a sustainable open banking body, and to address existing open banking limitations. That now looks set to kick off in September.

This work is crucial to ensure the fintech ecosystem remains healthy and thriving to meet the challenges and opportunities unlocked by future open finance legislation.

3 tipping points for change within ecommerce payment experiences

How to reduce ecommerce cart abandonment

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)